Why does Australia have so many live auctions?

And are they good for buyers? Investigating my most bizarrely popular tweet.

On my recent trip around the US, I learned that house auctions—Saturday morning events where half the neighbourhood rocks up to watch a fast-talking bloke palm off a property one ten-grand bid at a time—are mostly unique to Australia.

As I said in my tweet: this shook me to my core—and so I decided to investigate: why does Australia have auctions, and who are they good for?

Auctions were first required by law—and have remained popular since

Land auctions were first mandated by the British Colonial Secretary in 1831

In the early years of the Australian colony, most land was distributed by grant. Free land was used to entice settlers, awarded to military officers, and even given to ex-convicts who had served out their term.

When a single male ex-convict was freed, he would often be granted 30 acres. If he had a wife, 50 acres. If he had two kids—a whopping 70 acres. If you’re like me and no good at thinking in acres, let me help you out: 70 acres is 283,000 square metres. The mythical quarter-acre block is about 1,000. The median lot size in inner-city Melbourne is around 500 or less.

This immense generosity was reigned in over time, and on January 3, 1831, land grants came to an end all together.

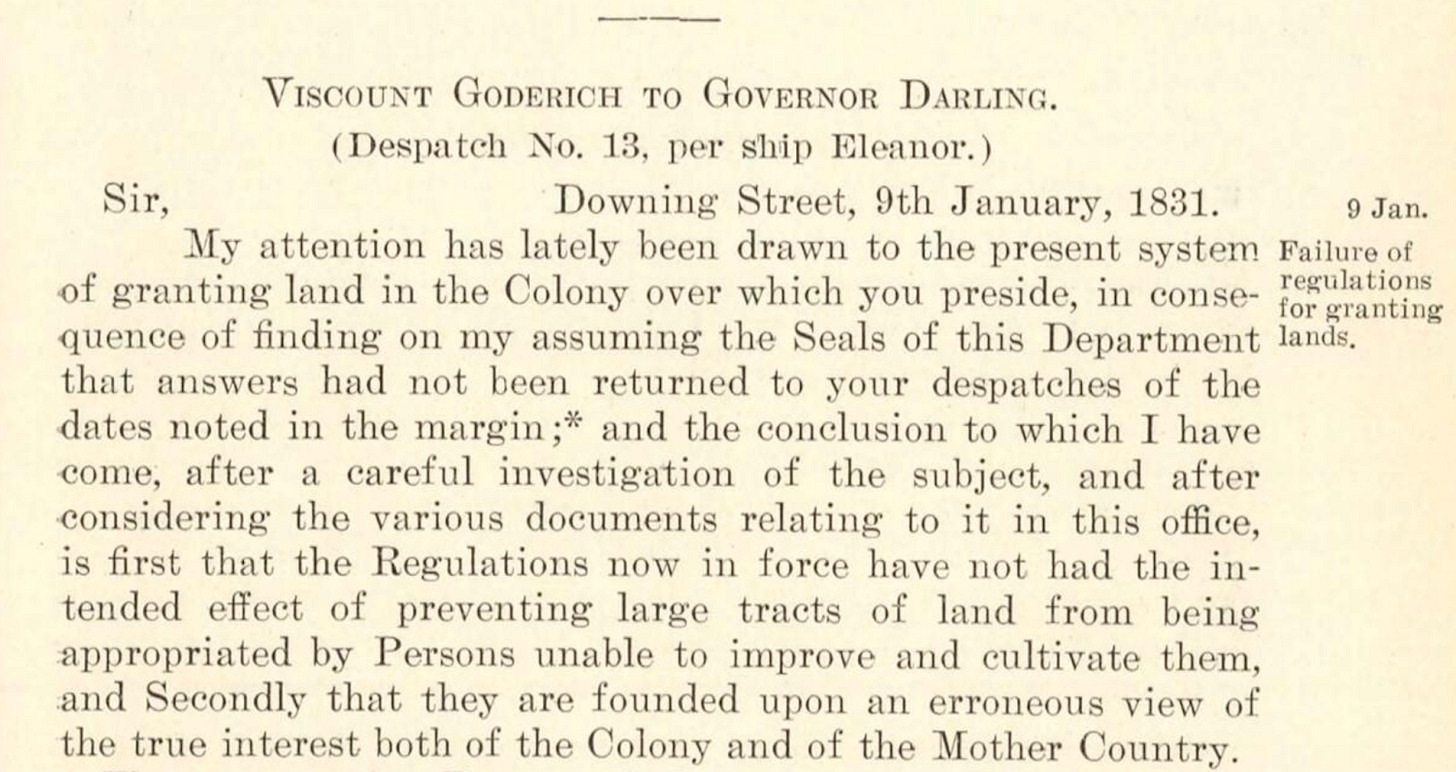

Previous Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Viscount Goderich was serving as Colonial Secretary at the time. And so it was within his purview to issue a despatch to the colony, expressing dismay at the way land was being allocated and offering a correction.

The Viscount’s feeling was that the Crown’s wanton allocation of large land tracts was extremely inefficient. “The Regulations now in force,” he wrote to the Governor of New South Wales, “have not had the intended effect of preventing large tracts of land from being appropriated by Persons unable to improve and cultivate them.” Basically: the land they gave away for free was not being well-used.

Goderich was charmingly dry about the whole state of affairs. He wrote: “This result does not surprise me”. Me neither.

The letter in full is an interesting record of Australian cities’ path-dependency. Within its few pages the Viscount expressed alarm at the way settlers had spread themselves out across the land, due to the large acreages the Crown had granted them:

These two apparently inconsistent evils of a high price and of a want of demand lead me to believe that cultivation has been too widely extended, and that it would have been more for the interests of the Colony, if the Settlers, instead of spreading themselves over so great an extent of territory, had rather applied themselves to the more effectual improvement and cultivation of a narrower surface.

With concert and mutual assistance, the result of the same labour would probably have been a greater amount of produce; and the cost of transporting it to market would have been a less heavy item in the total cost of production. A different course however has been pursued, chiefly, as it appears, owing to the extreme facility of acquiring land.1

The land granting process may in no small part underpin the remarkable lack of density in Australian cities today: from before our nation began, households were incentivised to sprawl further and further away from each other.

But we are getting sidetracked. We now know the Viscount’s diagnosis of the problem: giving random people large amounts of land for free creates suboptimal outcomes. So what is his solution?

I am sure you must have found the impossibility of giving satisfaction to all the applicants for land and of reconciling contending interests, and that you will gladly be relieved from the irksome and ungracious task of endeavouring to do so.

[...]

The measure, to which I allude, is that of declaring that, in future, no land whatever shall be disposed of otherwise than by sale, a minimum price (say five shillings an acre) being fixed, but this price not to be accepted, until upon proper notice it shall appear that no one is prepared to offer more, the highest bidder being in all cases entitled to the preference, ten per Cent on the whole of the purchase money to he paid down at the time of sale, and the remainder at an early period after the sale and previous to possession being granted. This last Regulation I conceive to be of great importance, and it ought uniformly to be adhered to.

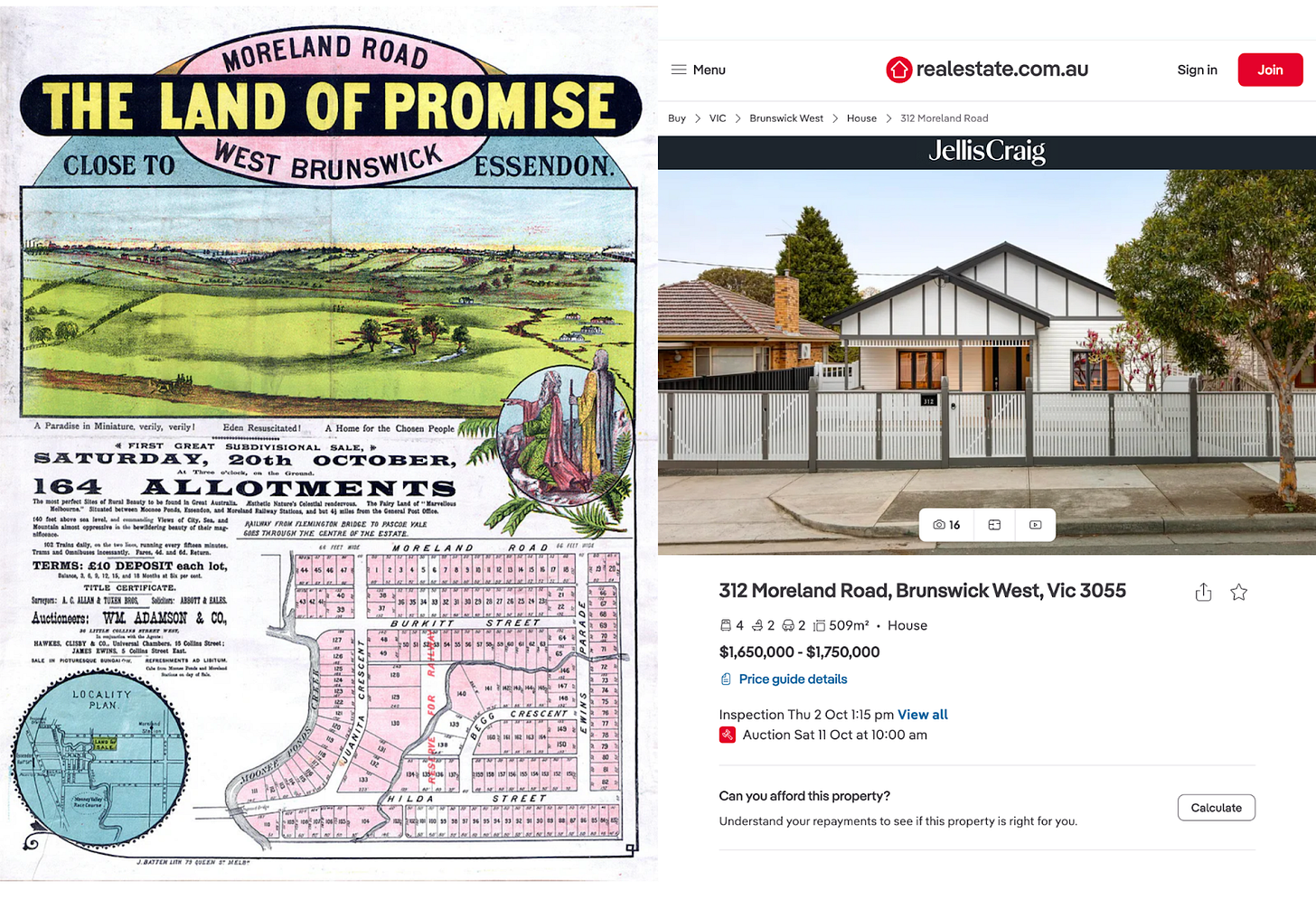

And so the colony began to sell all land by public auction.

Auctions were quickly popular, and have remained so

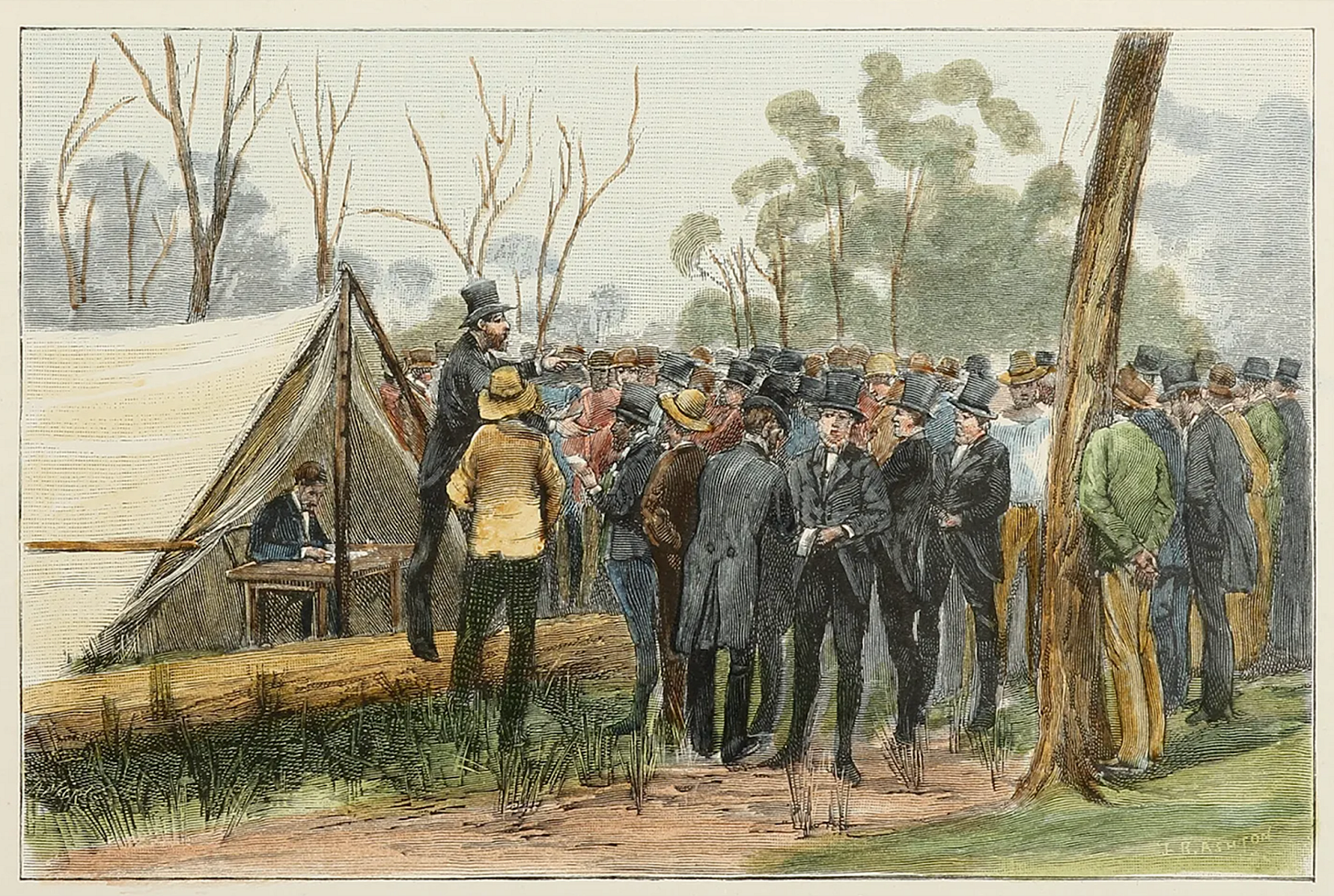

People started hanging out at auctions almost immediately, and as the majority of auctions moved from the Crown to the private market, the spectacle remained. Per Dr Richard Gillespie for Museums Victoria:

The new suburban estates spread along the expanding rail and tram lines; prospective buyers of land were lured with the offer of free railway passes and lunches of chicken and champagne prior to the auction.

These sorts of incentives still exist as part of the property sales pipeline, though mostly for boutique off-the-plan apartments, which are not typically auctioned.

Nonetheless, Australians remain happy to rock up to Saturday morning auctions. Bad coffee, it seems, is a fine substitute for champagne.

In 2021, more than one in eight properties were sold at auction. In Melbourne, Canberra, and Sydney, this number was more than one in four.

Interestingly, very few properties go to auction in Perth or Hobart. To the point where Domain—back when they used to publish a monthly auction report—excluded those two capitals.2

Why is that? The answer, once again, is regulation.

Who are auctions good for?

For sellers, auctions offer certainty

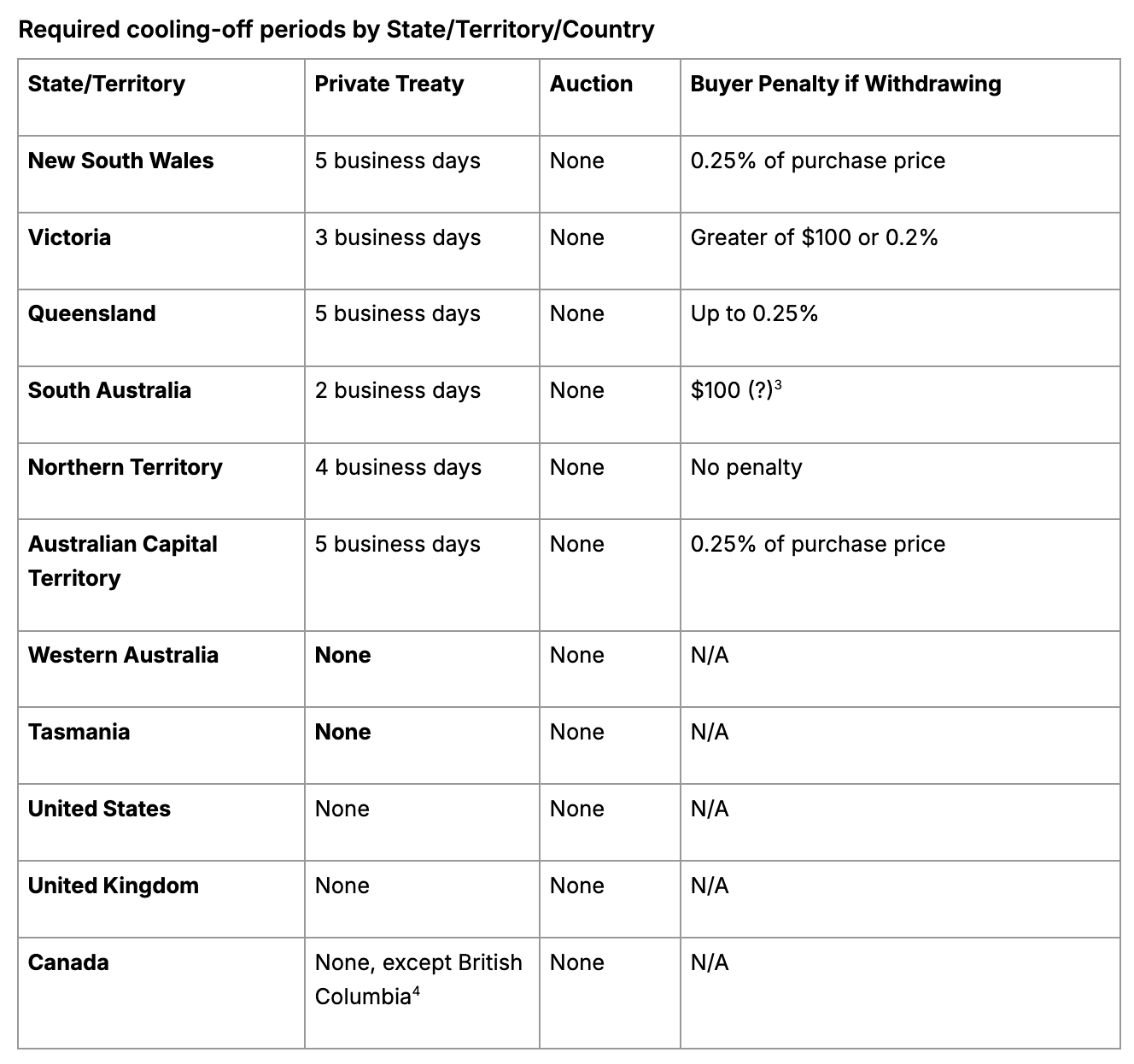

The crucial thing to know about house sales by auction is that they are binding. There is no cooling-off period, meaning that neither party can back out of the sale once the deal is signed.

At an auction, the sale is unconditional from the moment the hammer falls: the highest bidder is legally bound to purchase, and they must do so on the spot.

In Australian states outside of WA and Tasmania, the benefits of auctions for sellers are obvious: the lack of cooldown period offers greater certainty.3 But in states where auction and private treaty contract requirements are identical, the additional costs of an auction—property setup, fees, auctioneer, weekend hassle—offer no extra benefit to the seller.

But what about buyers?

For buyers, auctions offer tradeoffs

The obvious benefit of a live auction is price transparency: each buyer knows exactly what the other buyers are offering. In closed negotiations, information is asymmetric: the seller knows all the offers, and each buyer knows only what they hear from the seller. This leaves competing buyers in private treaties vulnerable to overbidding.

On the other hand, the rush of a bidding war can also lead to overbidding, and result in a phenomenon known as the winner’s curse, in which the victor of an auction overpays and as a result experiences suboptimal long-term outcomes. This phenomenon is not limited to property—it’s also been observed in places like stock market initial public offerings.4

But the most recent Australian study I can find—a 2012 paper by Frino, Peat, and Wright—found that when properly controlling for relevant factors, there was “no significant difference between prices of properties sold at auction to those sold by private treaty”.5 So it kind of feels like a wash.

Auctions are fine, actually

The majority of objections to Australian home auctions are aesthetic: the spectacle, perhaps, feels like a gross extension of our property-obsessed culture. And maybe it is.

But when you look at both the history and the outcomes of auctions, the whole thing looks a lot more like a cultural curiosity than a substantive factor in the successes and excesses of our inflated housing market. But it’s an interesting curiosity nonetheless.

This is a more in-depth engagement with land markets and price signals, by the by, than you’d expect in any modern urban planning department.

Darwin is also excluded, but that’s likely due to overall low sales volume.

Information about South Australian buyer withdrawal penalties are mixed, which is weird. I’d love this part of the table corrected, if anyone can confirm the actual state of affairs. I also did not delve too deep into differences between Canadian provinces.

How are your Guzman returns going?

These results correct those of a 2010 paper by the same authors.

Interesting to get this background to why Australia is peculiarly likely to have auctions. For a future post maybe I'd be interested to dig more into the particular auction mechanics that seem to defy standard auction procedure and favour vendors: things like not having to disclose your minimum selling price, allowing dummy bids, and not having to accept the highest bid (!). While an advantage of auctions is the transparency the same transparency doesn't currently apply to the vendor.

And all the neighbours show up because we are a nation of stickybeaks! Fascinating article.