No, Australia does not need new cities

We have a lot of cities. We just aren’t using them well.

The first serious1 call for creating new Australian cities came from Greg Kaplan in a recent—excellent—episode of the Joe Walker Podcast. My Inflection Points colleague Manning Clifford recently took this further in his own article, where he laid out that Australia might be better off if we had more cities and if those cities were very specialised.

I’m not enamoured with either take. The obsession with new cities, I think, comes mainly from the fact that thinking about new cities is a lot of fun. In practice, of course, creating new cities is very costly, and rarely ever works. This is because cities are labour markets, and labour markets are difficult to create from scratch. The most recent example of a new Australian city is Canberra, a place that only exists because the government forces the bulk of the public sector to work there.

This gets to the heart of the new city problem: individuals and firms need a good reason to move. For any new city to succeed, it must offer some combination of resources or amenities that existing cities do not. Otherwise, no one will go there.

It is difficult to imagine how new cities might differentiate themselves in the Australian context. Local governments have limited ability to meaningfully vary policy,2 and it’s not like a new city can offer meaningful tax and transfer incentives to entice would-be residents. A new Australian city would just have to be really, really valuable on its own merits—but it almost certainly wouldn’t be.

All of this is okay, of course, because I come bearing good news: we do not need to create new cities.

This article will do two things: first, it will weigh in on the recent new-city discourse.

Second, it will lay out the fact that Australia actually has a large number of cities. We just don’t use them very well, and could very easily make that change.

Setting the “new city” record straight

Australia is not particularly centralised

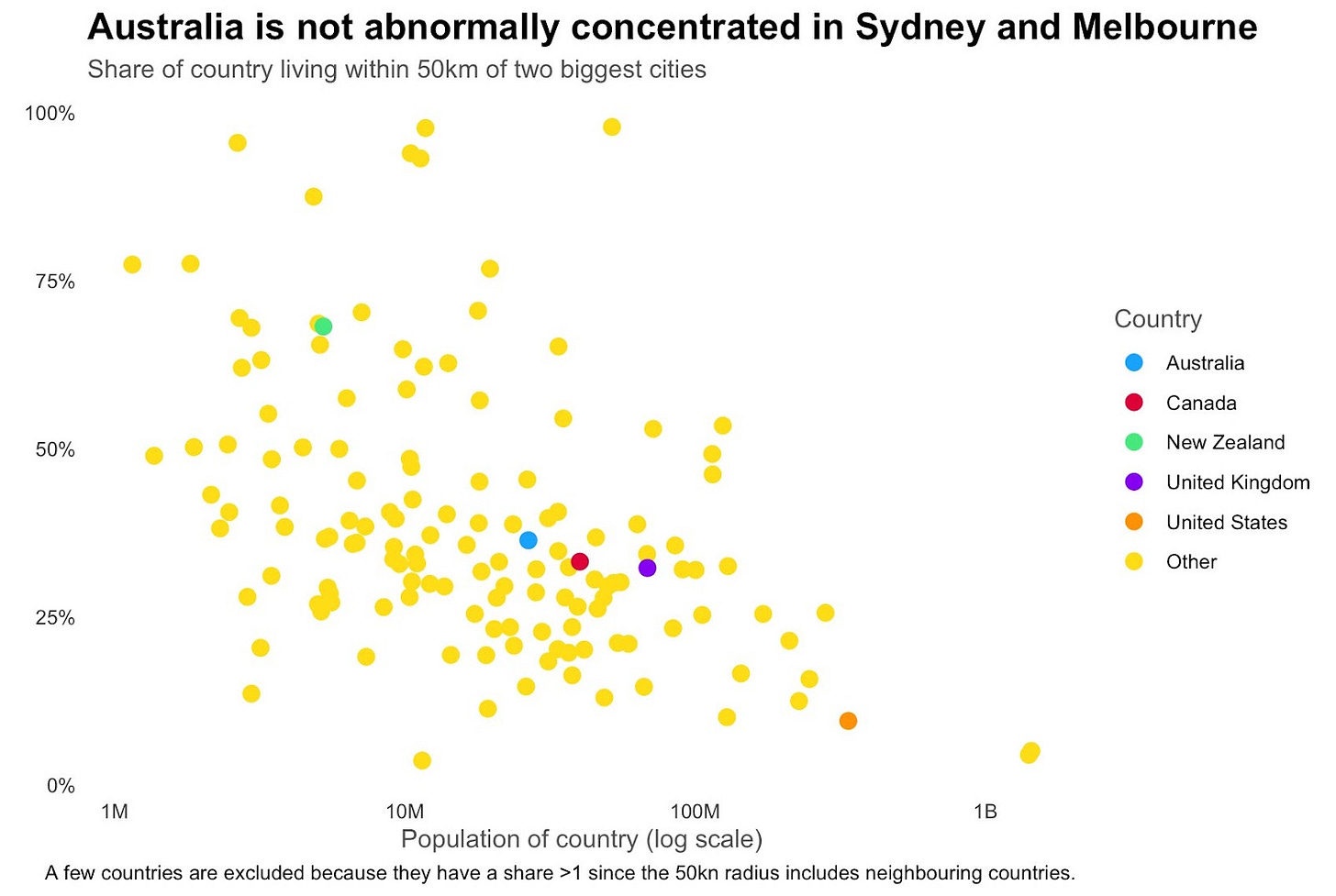

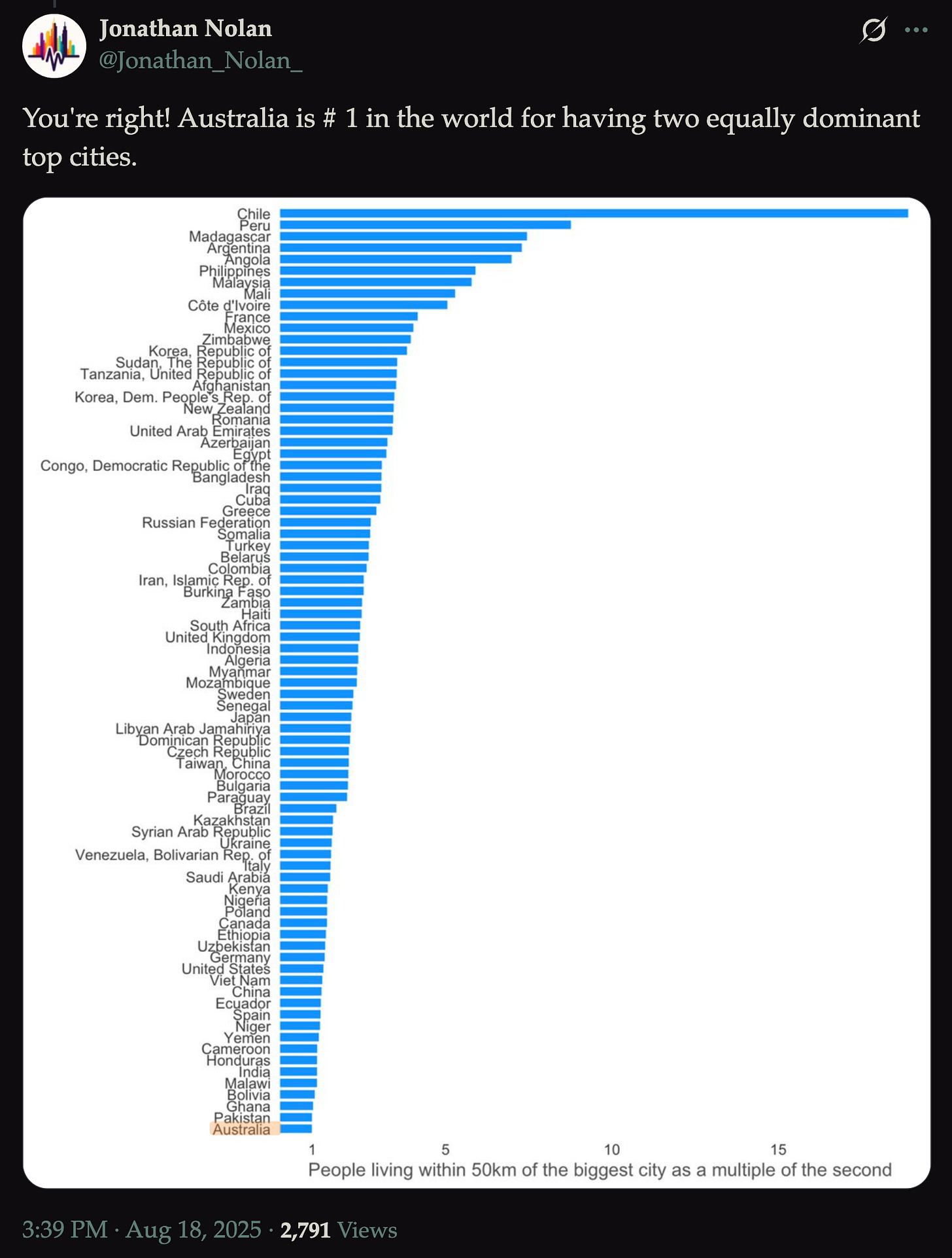

One of the important things to remember is that Australia does actually have a lot of cities. City Density creator Jonathan Nolan laid this out, demonstrating that Australia’s centralisation in just two cities is not actually unique.

One mildly interesting fact is that because Sydney is only 1.03× the size of Melbourne, Australia’s top-two cities are most similar in size when compared to any other top-two city pairs internationally.

But while we are ranked first on this metric, we are by no means an outlier—meaning that this is more of a party fact to tell your uncle this Christmas, rather than a north star to inform your next policy submission.

Specialised cities are not necessarily better

Manning’s article focuses on Marshallian externalities—the agglomeration benefits of specialisation, often driven by a few dominant firms. I think this is a fine story to tell, but it is incomplete, and understates the reasons we might think that Australia’s generalist cities are actually internationally successful, and well-placed to continue that success.

To get a more full understanding of how cities drive growth, we can look to de Groot, Poot, & Smit’s 2009 paper Agglomeration Externalities, Innovation and Regional Growth: Theoretical Perspectives and Meta-Analysis. Crucial to understanding this meta-analysis is that there are three kinds of agglomeration externalities:

Marshall-Arrow-Romer externalities: the role of concentration and specialisation

Porter externalities: the role of competition intensity

Jacobs externalities: the role of diversity and cross-sectoral spillovers

Focusing only on Marshallian externalities, then, is incomplete: there are other ways we might foster healthy, growing cities. Analysing 322 articles, de Groot and friends looked at exactly this, and they found some pretty stark results: almost 4 in 10 studies found that specialisation has a negative impact on growth outcomes—whereas only 1 in 10 found a negative impact from diversity.

The overall evidence of the meta-analysis based on a simple counting of conclusive effect sizes reveals that relatively many primary studies conclude in favour of significantly positive effects of diversity and competition on growth. No clear-cut evidence was found for the effects of specialisation.

Economically diverse cities are the most successful cities.

Diversity is more often the key to a city’s success than specialisation.

This is a big deal. Manning may be right: there are certainly some cases where specialisation can yield enormous upside. But it’s also clear that specialisation carries large risks, and I’m not sure they’re risks worth us taking as a nation. If it were advantageous for industries or firms to centralise in single Australian cities, they would have likely already done so.

As the de Groot meta-analysis demonstrates, a lack of specialisation does not indicate that our cities are worse off than the counterfactual—if anything, it may explain their relative strength. The Australian economy has gone a long time without downturn—and our cities have each done the same, in no small part because diversity creates resilience to shocks.

I think where Manning’s article is most correct is when it discusses the failures of Australian industrial policy. What it misses is that policy attempting to create specialisation among our cities may just be yet another expensive exercise in picking losers.

Australia has many under-utilised cities

Let’s say you’re unconvinced by the above, and still think we need new cities. You may, for instance, be under the impression that Australia has relatively few sizeable cities compared to peer nations. But this is also not really the case.

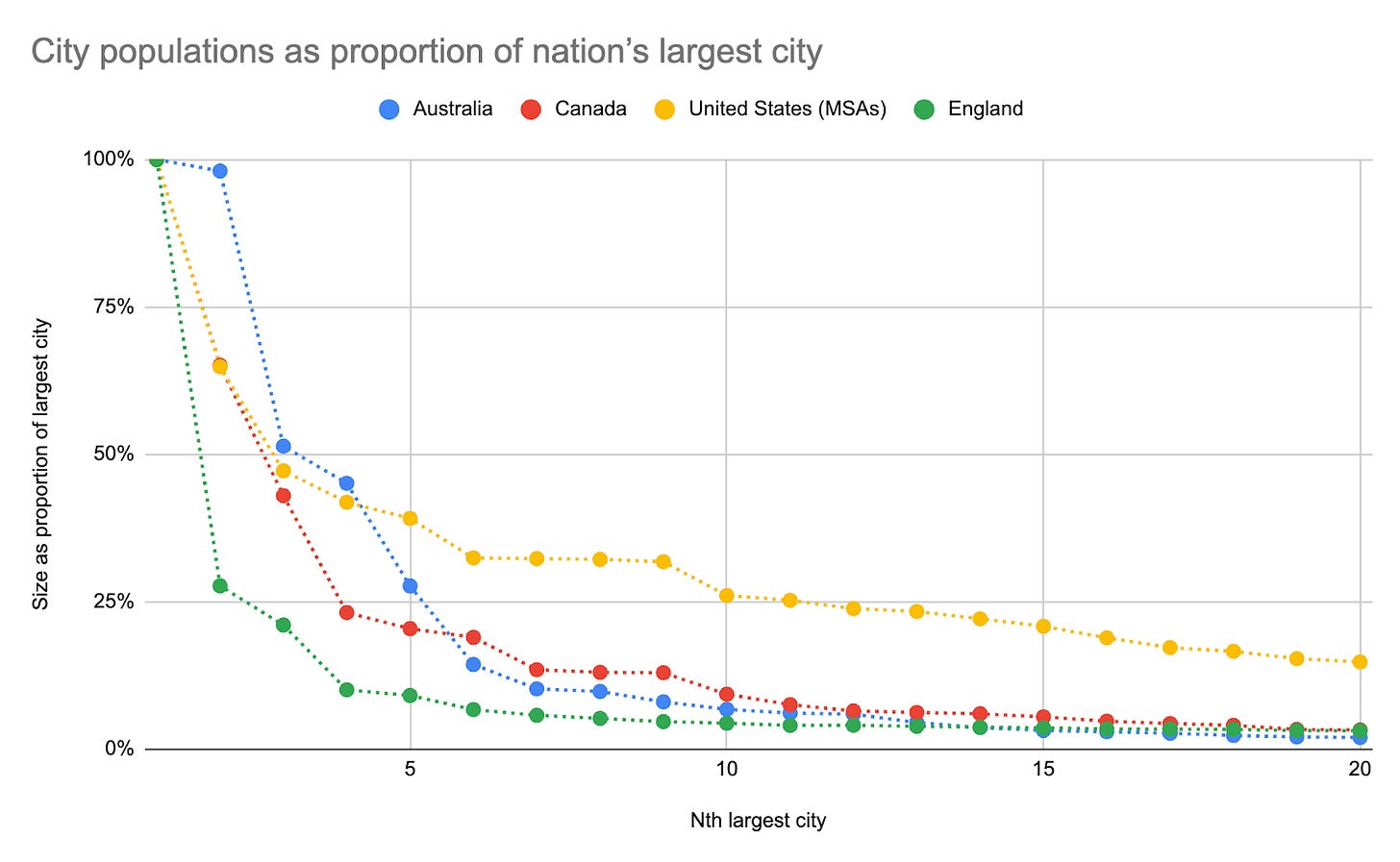

The relative size of Australian cities stacks up globally

In the chart above, you can see that Sydney and Melbourne are very close to each other in size—but that the following drop-off in Australian city size is not all that precipitous.

It is only in 5th place where we see Adelaide drop below the US’s equivalently ranked Dallas, and at 6th where the Gold Coast drops below Ottawa in Canada. We stay above England until 15th, where Cairns as a proportion of Melbourne drops just slightly below Bradford as a proportion of London.

We aren’t the United States, but crucially—neither is anyone else. That said, how might we get closer?

Small Australian cities are subject to stringent land use regulations

Australia’s 18th-largest city is Ballarat. Its origins of growth can be found in the gold rush of the 1850s, and between 2014 and 2024, it remained the 12th fastest-growing Australian city. But the city is subject to significant land use restrictions that force most housing development outside the city, and restrict the development of commercial capacity.

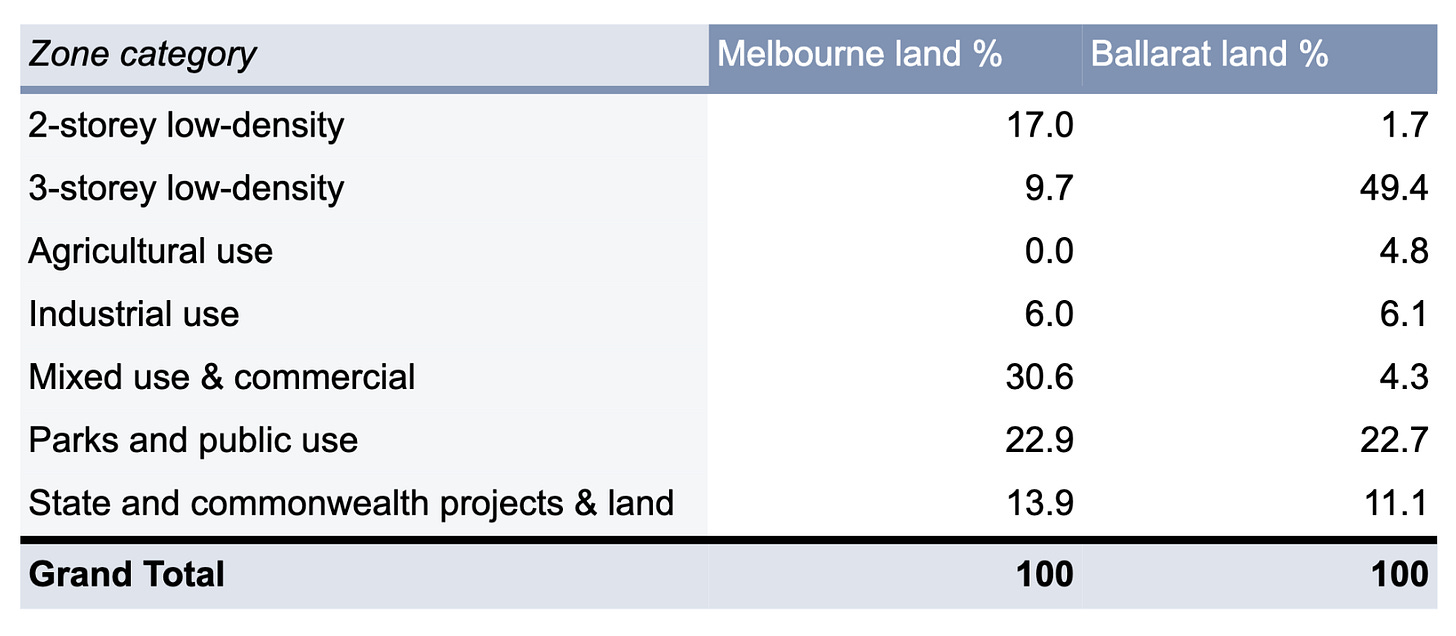

YIMBY Melbourne compiled Ballarat’s zoning data as part of our submission to the Inquiry into the supply of homes in regional Victoria. Our focus was on residential zoning, but because our mixed use density category is a combination of commercial and mixed-use zones, you get a clear idea of just how prohibitive the zoning in Ballarat is for new entrants.

While Melbourne and Ballarat allocate similar amounts of land to industrial use, Melbourne enables mixed-use and commercial development on more than 30% of its land. Ballarat allows the same on just 4%.

Even if Ballarat wanted to specialise, it would likely struggle to do so, because the rules that govern its growth are prohibitive. The scarcity of commercial land will mean reduced availability and higher costs—not exactly the conditions for fostering innovation outside the big cities that one might hope to find after so many hours of inland travel.

We should enable all our cities to grow

Of course, Ballarat is just one city—but this story generalises across our nation’s regions.

The point I’m making here is one that the YIMBY movements of our nation’s capitals do not often have time to emphasise: that the restrictions our large cities face are faced in equal measure by our smaller cities. That in fact the case of Ballarat demonstrates that these restrictions may well be more extreme in our smaller cities. The NIMBYism of residents is almost certainly as fierce or more.

I mentioned earlier that I am wary about policymaking that tries to pick winners. By divvying up land arbitrarily, legacy planners have created an entire school of policy based around the idea that picking winners is a) desirable, and b) reliable. But it is neither of these things.

If you want new cities, or better cities, or cities that specialise—the policy prescription is the same: loosen land use restrictions in every city across our nation, and let people and firms vote with their feet. We should want to create the best possible set of Australian cities—but that requires letting people build them in the first place.

Serious in the sense that it came from a serious person and not a crank.

The main policy tools available to local governments involve restricting development, which is not very useful for creating new cities.

If I count as a crank, fair enough

https://www.kvetch.au/p/a-new-hong-kong-in-australia

There’s a ton of beach towns with a a tiny zone where you can build hotels/apartments. If you had by-right building to 3-5 stories you’d see a lot of growth right along the East Coast.